In Kolkata’s New Town, the skyline catches fire each evening, glass towers blazing gold, sharp-edged against the fading light. This is the city’s newest pride, where ambition hums in silent elevators and clean roads stretch without memory. But beneath the shimmer, another story breathes. Hidden in plain sight stands a small college, modest in brick and mortar yet carrying the weight of a thousand unspoken dreams. It begins humbly, two floors of classrooms still smelling of wet cement, corridors echoing with uncertain footsteps, and grows quietly, like the neighborhood around it swelling with malls named after distant cities and gated towers whispering of Europe and California.

The college is not meant for those who live behind those gleaming windows. It is for their shadows, for the children of hands that never turned the pages of a book. The students are the first in families stretching back generations to sit in a classroom beyond school gates. Their homes huddle in narrow strips of villages wedged between luxury like wildflowers pressing through concrete. They have always been here, slowly fading into the city’s margins, becoming less visible with each passing year.

And so these students walk into the college carrying burdens heavier than their bags. They bring their families’ whispered prayers, the ache of invisibility, the trembling hope that this might change something. They come wearing borrowed confidence like ill-fitting clothes, stumbling over English words, uncertain whether to speak or stay silent, unsure even how to sit in rooms that still smell of possibility and fresh paint. Some stay. Others slip away like water through fingers, becoming delivery boys racing against time on buzzing scooters, sales staff smiling behind glass counters in air-conditioned temples of commerce, cashiers whose hands count other people’s money. The college grows, two floors become four, but the student count barely rises. Every year, the struggle repeats.

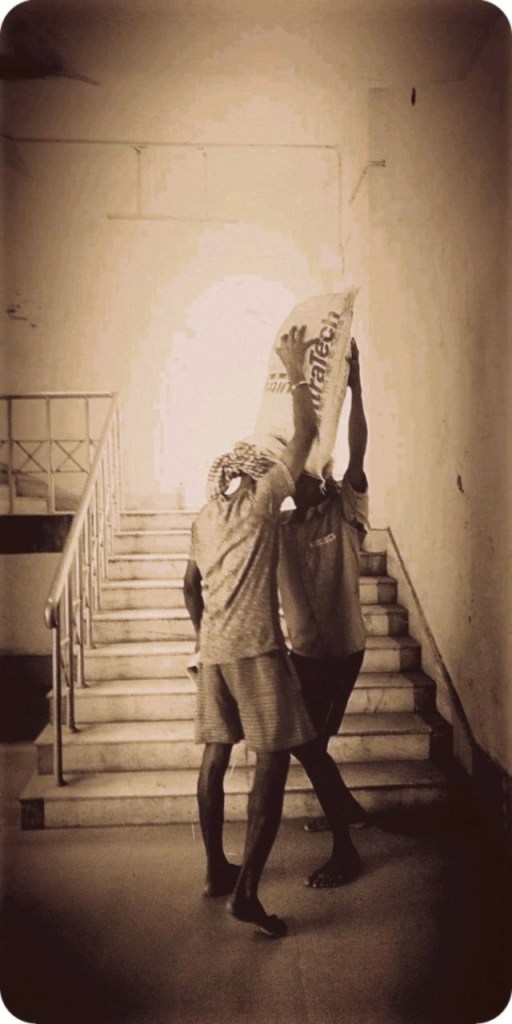

But what never repeats is the memory of those who raised these walls with their own flesh and bone. Before there was a roof over anyone’s head, before a single book was opened within these walls, there were men living under blue tarpaulin that snapped in the wind like desperate flags. Their children played in the dust, small bodies dancing through construction debris, while their wives cooked over stacks of bricks arranged into makeshift stoves, smoke rising into an indifferent sky. These were workers who had traveled from villages whose names nobody here would recognize, searching for work and worth in equal measure. They carried bricks on shoulders that would ache for years, hammered steel with hands that would never heal properly, balanced on unguarded ledges with nothing between them and the ground but faith and necessity. When the last brick found its place and the final tile gleamed under inspection, they gathered their blue tarpaulins and left quietly and without ceremony. Their stories would soon dissolve into the city’s relentless noise.

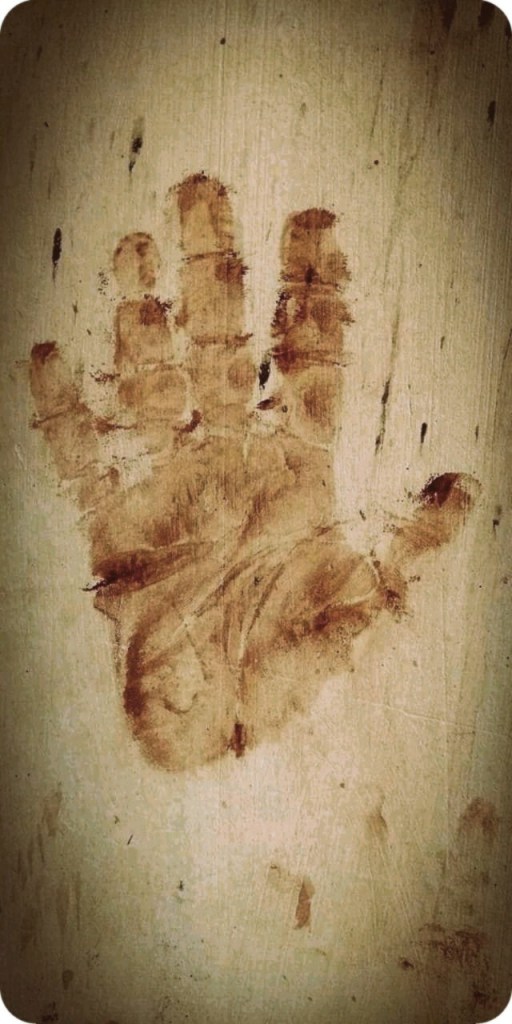

Sometimes, though, traces remain like a muddy handprint on a stairwell wall, or a scribbled name in a corner of the basement. One such handprint was found on the back wall outside the chemistry department, dark against the pale plaster, as though someone had paused to steady themselves before walking away. In the principal’s chamber, names of past and present heads of the institution are engraved neatly on a plaque. Each successor adds a line to the lineage, but nowhere is there a mention of the ones who laboured in the sun and rain to raise this structure from raw earth.

This forgetting is not new. It is ancient as pyramids, old as the first wall ever built. Bertolt Brecht once asked a question that still echoes, who built the seven gates of Thebes? History remembers the kings, but the workers’ hands remain nameless, their calloused palms erased from every monument. Who built the pyramids that still stand against time? Who laid the bricks of Rome, city of emperors and marble? Whose arms bled in silence, whose backs bent without breaking, to raise monuments that others would later claim, preserve, and write themselves into?

When the builders of the college moved on, after the last brick was laid and the floor swept clean, only that handprint outside the chemistry department remained. It was the final, fading trace of a life briefly etched into concrete. That too would be painted over before the inspection, quietly erasing the last mark of a builder who slipped into anonymity without ever being known.

Leave a comment